Otherwise known as Iliotibial band syndrome, runner’s knee is a common condition in the distance runner. Find out from physio Mark Buckingham how to deal with this often painful condition.

The problem presents as pain on the outside of the knee and over the kneecap. It is often difficult for patients to be specific about where they feel it. It is an achy sort of pain that builds up when running – more often sore to start. It can ease up as you run, only to be sore later after you have stopped, especially after sitting for a bit then trying to bend the knee.

There is sometimes a small bit of swelling but not a lot as there is nothing damaged, just inflamed The knee feels stable but can be sore to fully bend. The knee cap often feels tight and ‘odd’, as if it is not running freely. Rest does not help cure it in all but the most inflamed cases.

The cause of runner’s knee

The outside of the thigh has a taut structure called the Iliotibial band (ITB) which stretches from the top of the hip to the top of the shin bone and to the outside of the kneecap. As it passes over the outside of the bottom end of the thigh bone it presses against the ‘knuckle’.

The ITB is made of fibrous elastic tissue and its job is to act as an elastic band. When the leg goes behind you it tightens and as the foot leaves the floor the elasticity helps to swing the leg forwards. It adds to the efficiency of our walking and running. However, it can also cause problems, especially if it is allowed to get too tight or if the control of the hip is poor.

In the case of runner’s knee there are a couple of theories as to the cause of the pain. The traditional one says that as the ITB’s elasticity reduces it increases the rubbing effect on the outside of the femur and this leads to inflammation and pain. More modern theory says that the end of the ITB is full of nerve endings, particularly the fat that sits around this area, and loss of control in the hip causes more strain and compression which causes the pain.

Traditionally a bursa or a fluid filled sack it described between the ITB. More recent anatomic evidence suggests no such thing. However, each time we take a step the ITB is tensioned. Roughly there are 1000 steps to a mile, so the friction or pressure soon adds up.

The ITB can become tight for a number of reasons. Sitting is a good way, cycling another. Prolonged periods with the hip flexed like desk jobs and travel. Other issues are problems around the pelvis with the sacro-iliac joint and hip joint issues which affect the motion and direct trauma which makes the band less elastic. If you see a physio all these things should be checked out.

I would like to clarify what I mean by tight. The impression this gives is that it loses its length. In the case of the ITB I mean really that it loses it elasticity. An important distinction, and whether you subscribe to the friction or compression theory, loss of elasticity seems to add to the pressure build up and thus the pain. Certainly mobilisation of the stiffness of the ITB empirically helps the condition.

Other factors which need to be taken into account – more by experience than research – are:

- Leg length differences, often seen as part of a sacro iliac joint issue ,

- Road camber - running on a down slope with the affected leg loads the ITB more

- Worn out shoes - particularly on the outside of the heel

- Run/gait - such as bow-leggedness or an impact point under the mid-line of the body.

The tests for runner’s knee

-

Where is it sore?

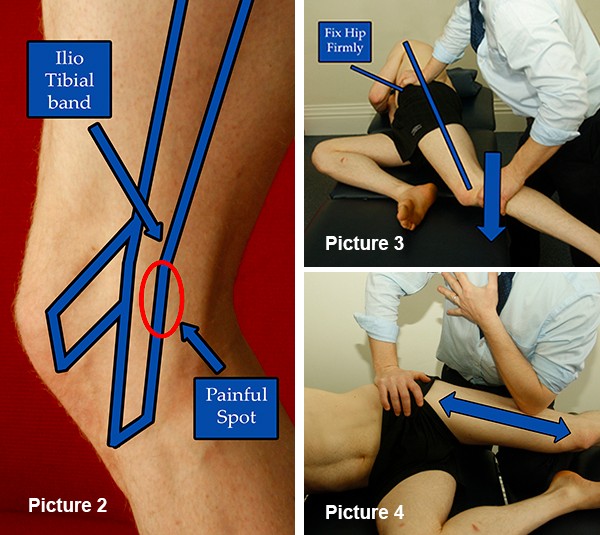

Picture 2 shows it well, but the tender spot is usually just below the fibrous band on the outside of the knee.

Hip mobility – iliotibial band length

Tightness in this structure is not easily felt by the sufferer as it has few stretch nerve endings. So whilst you know when a muscle is tight, it is difficult to know when the ITB is.

It is also a tough one to test. The Obers test (as shown in Picture 3) is the classic way but you need to be precise to be sure.

The patient lies on their side with the leg to be tested uppermost. The bottom knee is bent up. The tester takes the upper leg by the knee with one hand and places the other hand on the hip to keep it stable. It is important that this ‘hip’ hand fixes the hip and pelvis firmly.

The hand holding the knee lifts the leg horizontally backwards so that here is a straight line from the shoulder through the hip to the knee. The leg must be kept turned out so that the toes are at least horizontal if not pointing up to the ceiling.

With the patient relaxed allow the leg to drop to the floor/bed without rolling in or flexing at the hip. Keep that straight line!

The knee should easily touch the bed. If you meet resistance as you lower the leg and it seems to hover then you have a tight Iliotibial band.

Treatment for runner’s knee

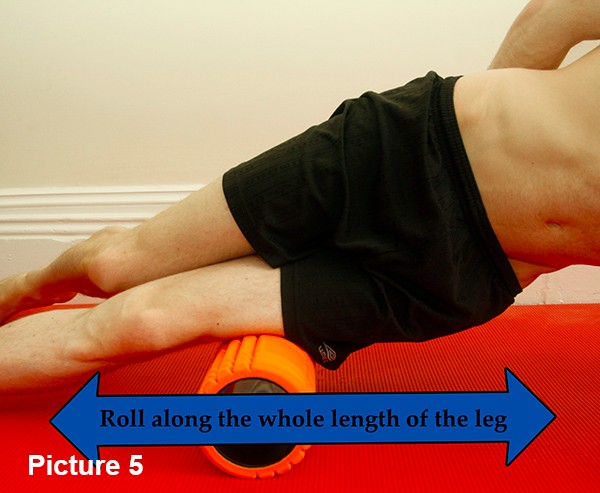

The most effective way of lengthening the ITB is by using a spray can, a rolling pin or such equipment as a foam roller. The position is shown in Picture 5. If it does not hurt then you are in the wrong place however you should avoid the very end of the ITB where the potential inflammation is as the pressure could make it worse. You need to roll for at least 2 minutes and 4 times a day to get the best result.

If you have a ‘friendly’ assistant you could ask them to mobilise it as well with firm massage (see Picture 4.) It will also be painful! A few minutes a day will suffice.

Ice, 15 mins every two hours, and anti-inflammatories as per the packet or as prescribed can help settle the inflammation.

Gluteal / Abductor strength

This is vital to the problem as weakness in the abductors has long been shown to be a big factor in ITB syndrome.

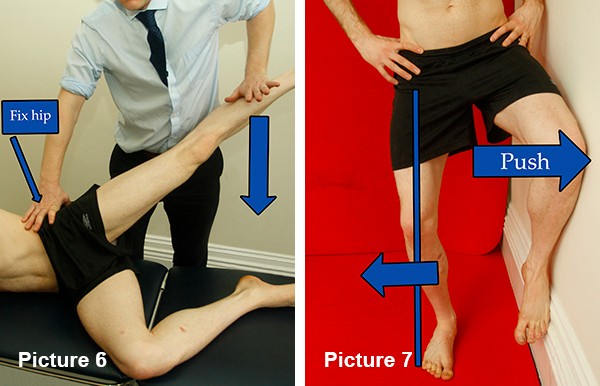

Glut strength . In the test position shown in Picture 6 with the leg held up and behind the line of the body you should be able to hold against someone pushing the leg down. Compare to the other side. If the leg can be pushed down then it is not strong enough.

The simplest way to start to strengthen the lateral glut is the wall exercise illustrated in Picture 7. Stand with the affected leg outermost and the other knee up against the wall. Bend the standing knee just in line with the toes and turn it out over the foot. Push the wall leg into the wall and brace using the gluts on the standing leg. The glut will take a moment to fire. Build from 2 minutes to 5 minutes.

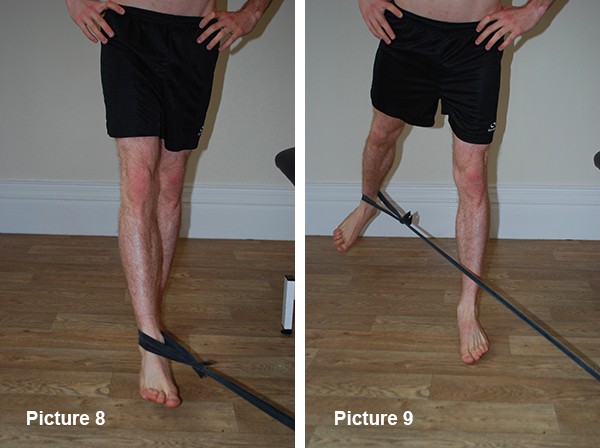

A method to purely strengthen the lateral gluts or abductors is using a band or cable pulley machine in the gym. Standing with the band around your ankle and attached firmly in front of you turn 45 degrees to face the band (see Picture 8.) Pull the leg to be worked on back along the line of the band (as in Picture 9.) The leg should be moving back and out behind you. Load this up so that 8 – 10 reps for 5 sets is as much as you can do.

Should I stop running?

Most runners’ knees will settle in 3 to 4 weeks of modified training within what you can do comfortably. There will be a tipping point of what it will cope with, usually around 20 mins. Swimming is a good alternative. Cycling tends to tighten the ITB when you are trying to lengthen it.

What to do if it does not settle

Firstly get it looked at by a physio with good experience in running issues. You should be assessed from the back down to the feet to find all the issues that are leading to the ITB getting irritated. The pelvis is important but hamstring and calf tightness and foot weakness can play a part.

My experience shows that correcting these points along with some deep work to the ITB will sorts out around 80 per cent. Sometimes however the inflammation has simply become too chronic and when you are happy the structural issues are corrected (i.e. the tests are normal and you have checked the other areas out fully) then a steroid injection may be indicated. Again you should be advised on this by your physio and referred to an appropriate clinician, such as a Sports Physician or Musculoskeletal Radiologist.